Federico Pardo’s unfiltered storytelling implores humans to protect Colombia’s vanishing primates

By ‘bringing the jungle to the city,’ the Colombian biologist and photographer creates space for humans to encounter his country’s most endangered monkeys.

Every time National Geographic Explorer Federico Pardo visits the jungle to document monkeys, he is struck by their beauty. Perched on a platform among dense forest foliage, he positions himself eye-level with where the primates will be and settles in. Waiting for them to arrive is hot and humid, the air riddled with mosquitoes eager for a bite, but Pardo sticks it out for the special moment: “When you see them in the trees and they’re up close, you’re like, ‘Holy cow, they’re so beautiful.’”

Pardo doesn’t quite remember when monkeys in particular became important to him. In fact, as a boy of eight years old, his first animal of fascination were snakes. His mother was a microbiologist who worked in a laboratory that produced antivenoms for snake bites, and she’d occasionally bring the young Pardo along for a visit. Seeing the snakes kept at the lab, he was enthralled. “I loved it,” he recalls fondly. “I think my love for nature comes from that interaction with snakes and through my mom.”

Coincidentally, snakes were also some of his first serious photographs. Taking his first photography classes in Montreal during a gap year after high school, Pardo decided to buy a pet python on a whim — they were legal, after all.

“So I had a snake in my apartment, and I was taking photo classes, so I started photographing the snake,” Pardo remembers. “It was just basic photography, through the terrarium and whatnot, but I remember those images becoming cool.”

He went on to study biology at Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia, and completed his thesis in the Orinoco region, focusing on bird-fruit interactions and evolution. There, he had his first face-to-face encounter with a group of howler monkeys. Luckily, he had his camera with him. “Those photos that I took that day,” he shakes his head. “I was like, ‘Wow, seeing monkeys up close is important.’ It’s something that really shakes you.”

Shortly after this trip, perhaps affected by those perspective-shifting howler monkey photos, Pardo decided to change course and pursue storytelling. “Maybe spending that time in the jungle, living with people from local communities, it made me realize that I wanted to go more down the communication side of science,” he says, compared to an academic route in which he’d be in dialogue predominantly with scholarly peers.

“I love so many things about biology and science, and I love photography. I think there’s a need to bridge two worlds, and maybe media will be the tool that I use to bridge those worlds.”

Today, Pardo is a seasoned natural history and wildlife storyteller with a brimming photographic and filmographic portfolio, including over a decade’s worth of experience in monkey conservation storytelling. He credits his successful career to a series of lucky breaks and serendipitous connections.

From internship to Emmy Award

In 2009 while pursuing his master’s degree in science and nature filmmaking, he met a group of people at a film festival supporting Proyecto Tití, a monkey conservation project in Colombia. They were happy to put him in touch with that organization, and soon he was working on his first monkey-focused film on cotton-top tamarins, of which there are less than 6,000 individuals left in the wild.

A year later, Pardo interned at National Geographic Television’s natural history unit. He was originally tasked with researching spider monkeys in the Peruvian Amazon, but in an unexpected change of plans, a producer offered Pardo the opportunity to film a sequence of the monkeys in Ecuador instead.

Pardo’s footage made it into the final show, “Untamed Americas,” which went on to win an Emmy in cinematography. “Some people joke that it’s the most successful career in the sense that [I went] from intern to Emmy Award,” he laughs, a bit embarrassed. “So it's been sort of a lucky career in that regard. Maybe the universe or destiny just wanted me to work with monkeys.”

For Pardo, photography offers an unsurpassed opportunity to be transported — physically for the photographer and figuratively for any viewer. He savors each chance he gets to visit an area he’s never gone before and relay back his experiences like a haul of treasure.

Especially at the beginning of his career, “traveling around Colombia with a photo camera meant documenting places that I had always dreamed about and couldn’t go to due to political instability in the country. Bringing those stories back to Bogotá and sharing them with friends and family was very important,” he says. “I love the expedition, I love doing the photos, and I love sharing the stories. All of that came together to push me to become a storyteller.”

The idea of being transported is integral to Pardo’s current Society-funded project, Salvando Primates, an immersive space that invites audiences to step into the world of Colombia’s endangered primates.

The day the project came to be, Pardo was mid-flight, pondering ways to create a bigger impact in monkey conservation. Thinking back on his previous work, “I realized that the needle wasn't really moving to the positive side of things,” he shares. “I was telling the stories, I was creating awareness, I was sharing with friends, family and audiences these important conservation messages, but the situation [for monkeys] was still dire.”

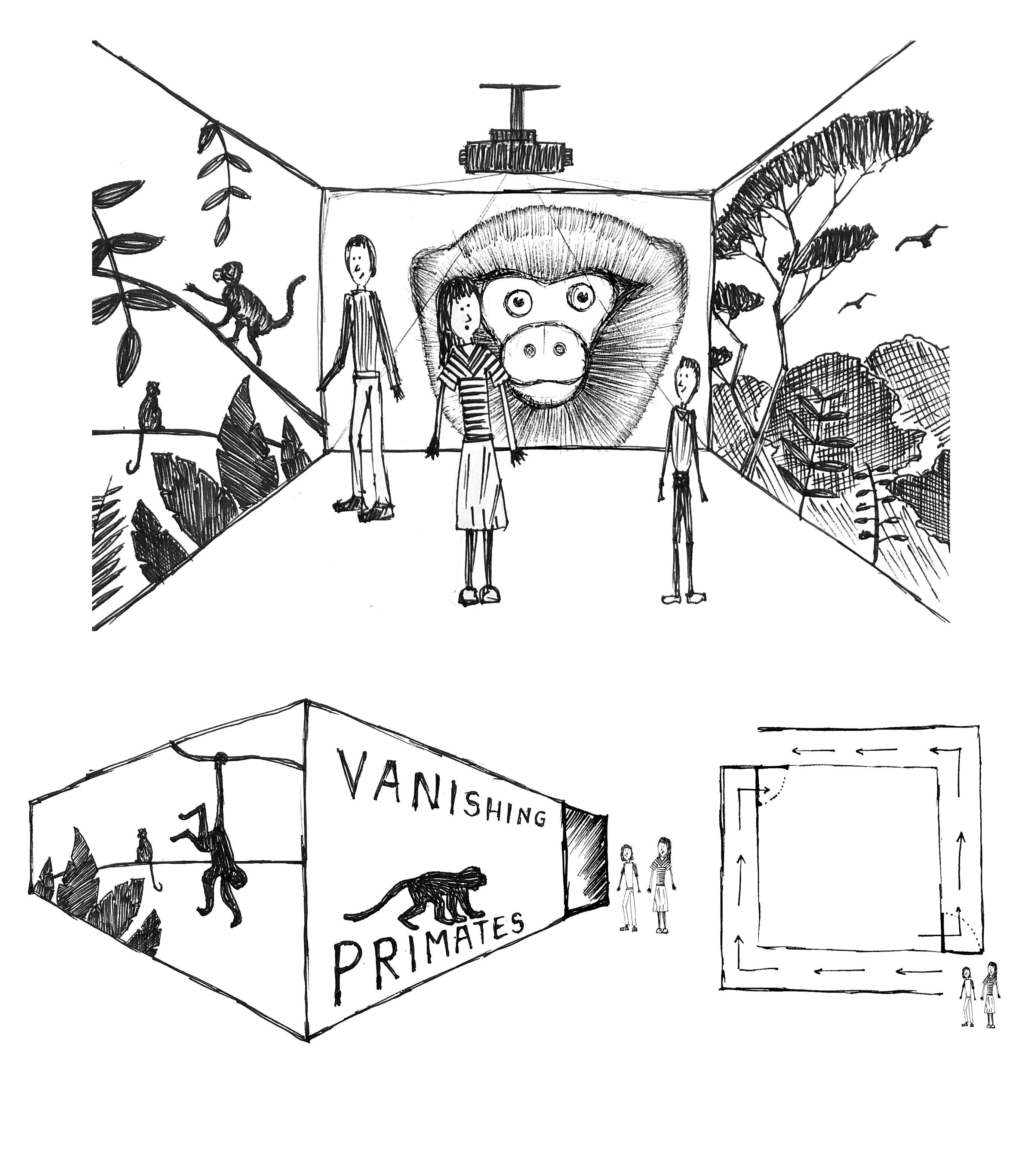

Then the idea came to him: bring Colombia’s jungle — and the critically endangered primates that call it home — to the city. On an airplane napkin, he sketched out a box-like space in which footage of wildlife could be projected onto all four walls. He envisioned an exhibition where “when people walked inside, it would be like walking into the jungle. A multimedia jungle in the city to tell the story of Colombia’s most endangered primates.”

Experiencing the jungle

Pardo sees primates as a vital hinge in the effort to promote healthy forests in his home country and around the world. For ecosystems like the Amazon rainforest and the dry forests populating Colombia’s Caribbean coast, monkeys act as an umbrella species, he explains. They require large territories with high connectivity and plentiful food sources, so protecting monkeys means protecting their forests and the many other species that depend on these biodiverse habitats.

Unfortunately, deforestation of Colombia’s forests is on the rise; Pardo calls it “by far the most important threat to monkeys” in his country. He echoes research showing that the Amazon may soon be reaching its tipping point at which it will be unable to provide the crucial environmental services that keep our planet in balance.

“The Amazon regulates the climate, the water cycle, so many things on a global scale that I thought maybe monkeys could be an important tool to help restore the Amazon, other forest systems and the planet’s health in the long run.”

Since then, Pardo has brought his multimedia jungle to life in the form of pop-up exhibitions. To date, he has reached more than 10,000 individuals in South America, from Salvando Primates’ inaugural opening in the Planetarium of Bogotá to TEDx Amazonia in Manaus, Brazil, and most recently, the Cartagena International Film Festival.

Telling the stories of four critically endangered monkey species — the cotton-top tamarin, the brown spider monkey, the Colombian woolly monkey and the Caquetá titi monkey — Pardo wields the exhibition as a means to evoke a deep sense of immersion in audiences, through a combination of familiar museum-like elements with an unadorned style of documentary storytelling.

I love so many things about biology and science, and I love photography. I think there’s a need to bridge two worlds, and maybe media will be the tool that I use to bridge those worlds.

“I wanted to do something different,” Pardo explains. “Normally, nature documentaries use the same formula to tell a story: this is a monkey, and it wants to eat this fruit, but to eat that fruit, it needs to go through this difficult adventure. There’s always a story arc attached to it, and that contrives a little bit of what you feel from seeing animals.”

In contrast, Pardo made efforts to film the animals in their environment simply as they were. “I made sure to get as much footage as I could of every little interaction of them being monkeys. I wanted people to see them up close, their hands, their tails, their eyes, their babies, playing, sleeping, feeding.”

When visitors enter the exhibition’s jungle, Pardo hopes that they feel it. “I don't want to tell them what to see or what to think. I want their emotions to be attached to this.”

The exhibition is a multi-part journey, taking roughly an hour to complete. First is an educational segment where visitors read plaques of information and hear from a docent about Colombian primates, their ecological roles, threats they face and the conservation actions Salvando Primates supports. Next, visitors are prepped to enter the main multimedia jungle and identify each of the four spotlighted monkeys, as well as seven additional monkey species and other wildlife they might see.

Audiences then slowly make their way into the immersive components. They walk through a sensorial tunnel, built from fabrics and infused with sound and scent, that leads into the multimedia jungle — a large projection theater. Here, Pardo’s 28-minute film screens ceiling-to-floor on all walls.

“It’s very ambient. It’s not necessarily a story,” Pardo describes. “Yes, there’s a predator, a jaguar that comes in and out, looking for the monkeys. Deforestation also is a big character, and we have a very intense moment where deforestation takes over and it’s very heart-wrenching, but you’re mostly just in love with the animals and this place.”

It’s this unfiltered quality of verisimilitude that coaxes genuine emotional responses from the audience. “We saw people crying in the exhibit. After witnessing the effects of deforestation, people come out and ask, ‘What can I do? This is terrible. I love it, but I hate it.’”

Beyond storytelling, onto conservation

Pardo’s goal has been to speak to the hearts of audiences with his storytelling, but in the process of making Salvando Primates, there have been encounters with the monkeys that left him just as moved.

To collect footage of Colombian woolly monkeys in the Amazon, Pardo and his team needed to build a platform at the perfect monkey-viewing vantage point, an emergent tree 90 feet off the ground. “For five days, I climbed up that platform every morning. Five in the morning, I would climb up, get there at 5:30, set up my camera and wait for the monkeys to show up.”

Eventually a family of about 20 monkeys appeared on the final three days. “It was unbelievable!” Pardo marvels.

“There’s a shot that I love of a mother with a baby monkey in the back, just climbing up trees,” he describes. He sat in amazement, watching them exist in complete ease before his camera. “They’re there. They don’t care that I'm scary. Yes, they look at you, but they’re doing whatever they do: feeding, napping, socializing, doing their thing. At that moment I was like, ‘Wow, this is the real deal. This is why I came to do this project.’”

It’s astounding that 14 years into his career, Pardo continues to experience moments that feel life-changing. “You see nature in its purest form. Trying to capture that somehow with cameras and footage and drones so hopefully audiences feel similar to how you did … I’d say [storytellers] have one of the best jobs in the world.”

Now that the physical aspect of Salvando Primates is up and running, Pardo is setting his sights on maximizing tangible conservation impact. Salvando Primates is not simply the immersive experience, he emphasizes. Equally as important is what he calls “the restoration engine.” For every individual who enters the exhibition, Salvando Primates commits to planting a tree in one of the four highlighted monkeys’ ecosystems.

“This way, it’s got an impact component. Deforestation is the main threat for the monkeys; we want to start reversing that,” he says. From the success of the past year’s traveling exhibitions, the team is planting and protecting roughly 8,000 trees across four strategic regions in Colombia.

They’ve partnered with four conservation organizations who Pardo considers the “true conservation heroes” for these critically endangered primates. “They are the ones on the ground with the tree nurseries, planting the trees in the ground or talking to farmers and landowners to stop deforestation.”

Pardo sees Salvando Primates as an articulator between citizens and conservationists. While his team may not have the experience and expertise to spearhead forest restoration, they’re more than happy to bolster the efforts of those already doing the work. “And I think it works great. It’s citizen-driven conservation done by conservation experts, through a multimedia exhibit,” he summarizes neatly.

But his ambitions run deeper than restoration projects. A multi-platform, open access educational program is being built out with activities for primary school teachers or parents to teach youth about the monkeys. And last year, the team launched their first storytelling for conservation workshop aimed at Colombian photographers, journalists and mural artists, with further iterations coming down the line.

Lastly, the team is thinking through Colombia’s first-ever monkey tourism route. Pardo envisions tourists traveling around the country to see these endangered monkeys, supporting local tourism initiatives. It’s slow going, Pardo says, “But I’m hoping by sometime next year, I can do the first trip myself and visit some of these locations.”

Each distinct element folds into Pardo’s greater hope of empowering large-scale conservation actions. He speaks with a palpable sense of urgency. “We are running out of time to secure a healthy planet. We have focused on awareness, education and entertainment, but impact has been left behind, and that’s why we’re in such a climate crisis.”

The coming years may see a new branch in Pardo’s career. On top of his own documentary work, he hopes that one day he’ll be able to dedicate a significant portion of his time towards bringing up the next generation of local storytellers through workshops and relationship-building.

“We need an army of storytellers working on conservation around the world … What if the people living close to the issues are able to tell the story for their community? Maybe we can start increasing tangible conservation on the ground," he imagines.

"It’s about decolonizing media, uplifting local storytellers and putting impact at the forefront, so we can finally see the needle moving.”

ABOUT THE WRITER

For the National Geographic Society: Melissa Zhu is a Content Strategy Coordinator for the Society with a love for language's ability to articulate the fullness of human experience. When she's not focused on advancing the nonprofit mission of Nat Geo, you might find her immersed in a good book.