What life is like when your brain can't recognize faces

The common neurological disorder affects roughly 2 percent of the population. Author Sadie Dingfelder shares her perspective navigating the world with it.

Fifteen pairs of eyes stared into the gloaming. An hour passed before someone spied the faintest wisp of smoke on the horizon. The wisp drew closer, becoming something larger, winged, and muscular: sandhill cranes the color of storm clouds, save for their smart red caps. They swirled around our bird blind, a converted shipping container set into the riverbank to hide us from the cranes, and dropped out of the sky in groups of two or three or five, landing gently in the Platte River in central Nebraska.

“It looks like one big mass of birds,” explained our guide from a conservation group called the Crane Trust. “But they actually stay in family groups for their entire migration.”

“How do they keep track of their mates?” I asked.

“They look alike to us, but I bet they look different to each other,” replied a woman in a green coat. I turned away from the birds to study her face. She had wide-set eyes, a ski jump nose, and short gray hair. Was she the same woman I was chatting with on the van ride here, the one who showed me pictures of her dogs?

She was flanked by two similar looking women, and all three were traveling with their own mates—men who were, to me, interchangeably outdoorsy, middle-age, and white. After the cranes melted into the inky darkness, we humans filed silently out of the blind and trekked across a muddy field, our careful footfalls drowned out by a choir of chirping frogs.

Back in the dining hall, we sat speechless, some of us near tears at the beauty we’d seen. As we began to put our collective wonderment into words, I noticed many of my fellow “craniacs” (our term for crane enthusiasts) were calling me by name. It wasn’t strange by any means. After all, we’d spent the past six hours together, chatting over drinks, getting settled in our cabins, and then packing ourselves tightly into vans. But, hard as I tried, I couldn’t draw forth any of their faces or names.

To my eye, humans are nearly as interchangeable as cranes, and I only recently discovered why. I have a neurological disorder known as prosopagnosia, or face blindness. Some people end up with this condition through brain injury, but most cases are genetic in origin—and this version, known as developmental prosopagnosia, affects 2 to 2.5 percent of the population. It touches nearly every aspect of our lives, from dating to networking to making friends, and yet it goes largely undiagnosed. This is because, like most people, folks with face blindness assume that everyone else sees the world the same way as we do. We don’t realize that other people perceive faces as distinctive and highly memorable. A case in point: Bill Choisser, who coined the term “face blind” in the late ’90s, once asked his partner, “Why do TV shows have so many close-ups of actors’ faces? How are we supposed to tell them apart if we can’t see their clothes?”

(Face blindness may be more common than previously thought.)

As a kid, all I knew was that I couldn’t seem to make any friends. I’d hit it off with someone one day and then treat them like a stranger the next. I later found out that my classmates, quite reasonably, thought that I was aloof, or weirdly hot and cold. To fend off loneliness, I would read constantly, usually series like The Baby-Sitters Club or Sleepover Friends. I dreamed of having not just one pal but many. I yearned for the safety of a flock.

In college I abruptly switched strategies—from treating everyone like a stranger to treating everyone like a friend. Walking to class, I’d stop and chat with anyone who so much as glanced my way. It was, I thought, a major improvement. So it went for another 20 years. I knew everyone without really knowing anyone, save a handful of best friends and a boyfriend, all of whom tended to be visually distinctive, or at least very loud. It never occurred to me that this might be a strange way to live.

Not long after I turned 39, I began writing down funny stories from my life, pushing to meet a personal deadline to write a book by 40. Since I was working at the Washington Post at the time, I sent drafts to friends who also happened to be award-winning journalists. They had questions: Why are you always lost? Why do you regularly have no idea who you are talking to? Why is your life shot through with so much ambiguity and confusion?

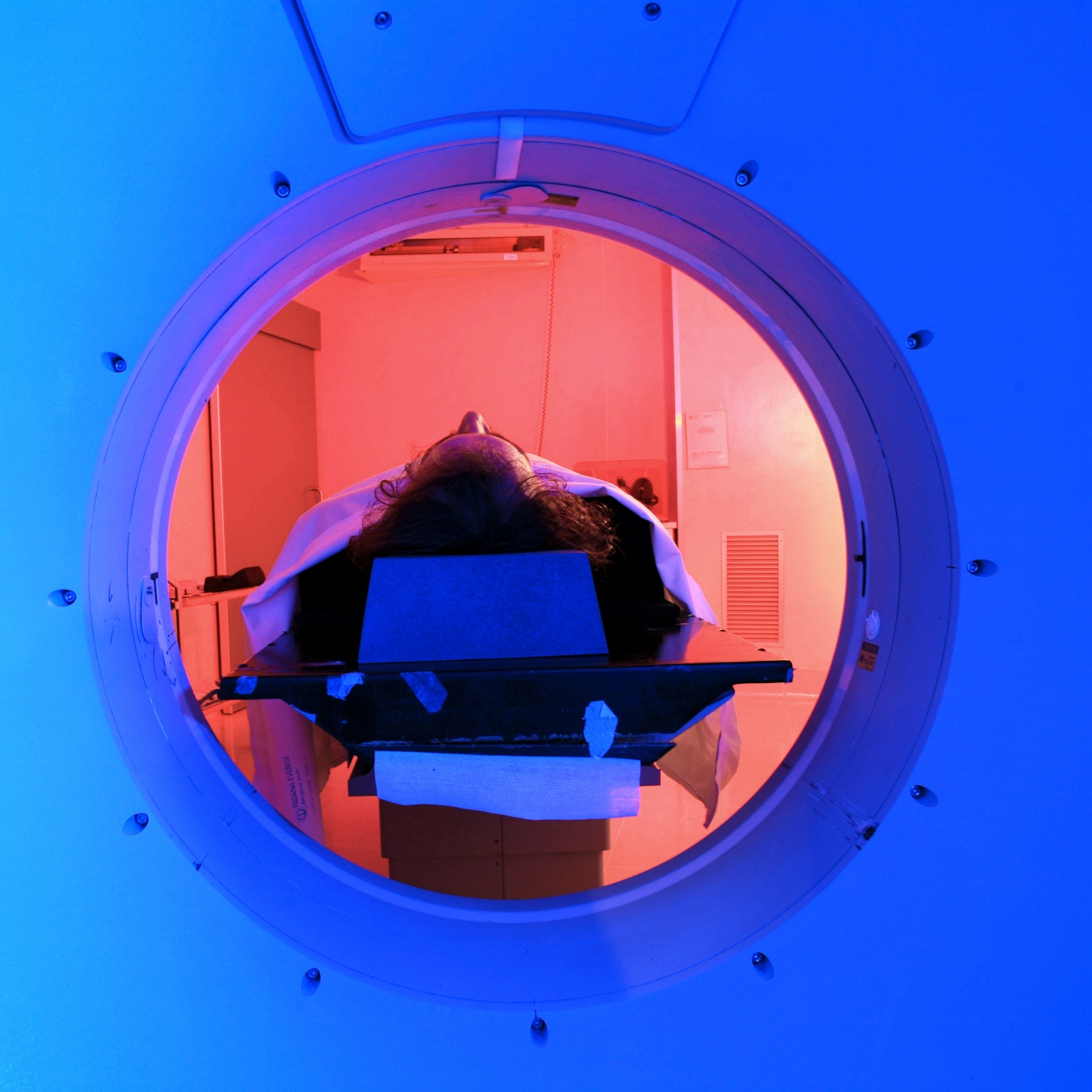

Other people might have consulted a neurologist, but as a science writer, my first instinct was to sign up for studies. One, run by researchers at Harvard, involved brain scans followed by nearly 30 hours of intensive face-recognition training. My scores in the program improved, but whatever skills I learned during the exercises did not translate to real life. Somehow, I figured out a work-around for tests that were all but impossible given my unusual brain—and this is how I (and most face-blind people) get through life. We figure it out. We adapt.

This is also true for the sandhill cranes. When humans replaced wetlands with farmlands, the birds adapted their diet to include crops like corn. The sandhills, however, are uncompromising in at least one regard: They need wide, shallow waterways to roost in—and that’s why, during much of the year, Crane Trust staff mow down saplings and prevent shrubbery from rooting along the riverbanks. As a result of this adaptability and assistance, sandhill crane populations have been steadily increasing every year.

While I don’t require much accommodation these days, except for the occasional name tag, I do worry about all the lonely face-blind kids out there—as well as people who have other neurological differences. What could we as a society do to make the world more hospitable to the largely unacknowledged diversity of human brains and minds? Where should we be clearing riverbanks?

It was late when we got back to our cabins, but I was still curious about the cranes. I skimmed a few papers before going to bed, and I discovered that cranes probably do look alike, even to each other. But their calls are distinctive. Each bird has its own signature sound, and their voices can carry for miles. This is how cranes keep track of their family members throughout their migration—not with their eyes but their ears.

I should have known. While the cranes looked the same to me, I noticed one particular bird that stretched its neck long and made a sound like an angry clarinet. “It looks like he doesn’t like where his family has roosted,” my friend in the green jacket observed. It was impossible to know, but I suspected she was right. The world is a cacophony of consciousnesses, all so different from your own. But sometimes, if you’re quiet, perceptive, and lucky, you can hear another singular voice piping through the din. I drifted to sleep that night feeling a deep kinship with the cranes, comforted by the knowledge that while my vision may sometimes fail me, my curiosity never will.

Sadie Dingfelder’s first book is Do I Know You? A Faceblind Reporter’s Journey Into the Science of Sight, Memory, and Imagination.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- What would the world look like without mosquitoes?What would the world look like without mosquitoes?

- Social media loves to villainize dolphins. Here's why it's wrong.Social media loves to villainize dolphins. Here's why it's wrong.

- How did wolves evolve into dogs? New fossils provide cluesHow did wolves evolve into dogs? New fossils provide clues

- This unorthodox method is saving baby parrots from extinctionThis unorthodox method is saving baby parrots from extinction

- A deadly disease that affects cats big and small found in U.S.A deadly disease that affects cats big and small found in U.S.

Environment

- ‘Corn sweat’—and other weird weather phenomena—explained‘Corn sweat’—and other weird weather phenomena—explained

- A sea tornado sank a yacht. We might see them more often.A sea tornado sank a yacht. We might see them more often.

- How billions of dollars are revolutionizing ocean explorationHow billions of dollars are revolutionizing ocean exploration

- Where to go stargazing in Chile according to a local astronomer

- Paid Content

Where to go stargazing in Chile according to a local astronomer

History & Culture

- Did Babe Ruth really ‘call’ this legendary home run?Did Babe Ruth really ‘call’ this legendary home run?

- The real history behind the legend of China's Monkey KingThe real history behind the legend of China's Monkey King

- How new technology transformed the American workforceHow new technology transformed the American workforce

- This secret Civil War sabotage mission was doomed from the startThis secret Civil War sabotage mission was doomed from the start

- This rare burial site reveals secrets about the Sahara's lush pastThis rare burial site reveals secrets about the Sahara's lush past

Science

- Why some say tennis is 'the world's healthiest sport'Why some say tennis is 'the world's healthiest sport'

- Your body ages rapidly at 44 and 60. Here's how to prepare.Your body ages rapidly at 44 and 60. Here's how to prepare.

- How do gold nuggets form? Earthquakes may be the keyHow do gold nuggets form? Earthquakes may be the key

- Astronauts getting stuck in space is more common than you thinkAstronauts getting stuck in space is more common than you think

Travel

- These are the must-see sights of Italy's Veneto regionThese are the must-see sights of Italy's Veneto region

- A guide to St John's, Atlantic Canada's iceberg capitalA guide to St John's, Atlantic Canada's iceberg capital