How humpback whales use bubbles as a tool

A new study confirms a theory that humpbacks are a tool-using species, as they deploy nets of bubbles to catch fish and krill.

Chimpanzees use sticks to fish for termites, sea otters crack open clams with a rock and dolphins use sea sponges on their noses for protection while foraging on the ocean floor. A new study adds humpback whales to the list of non-human species that use tools. Humpbacks may not only use a tool, but create it from their environment by blowing bubbles.

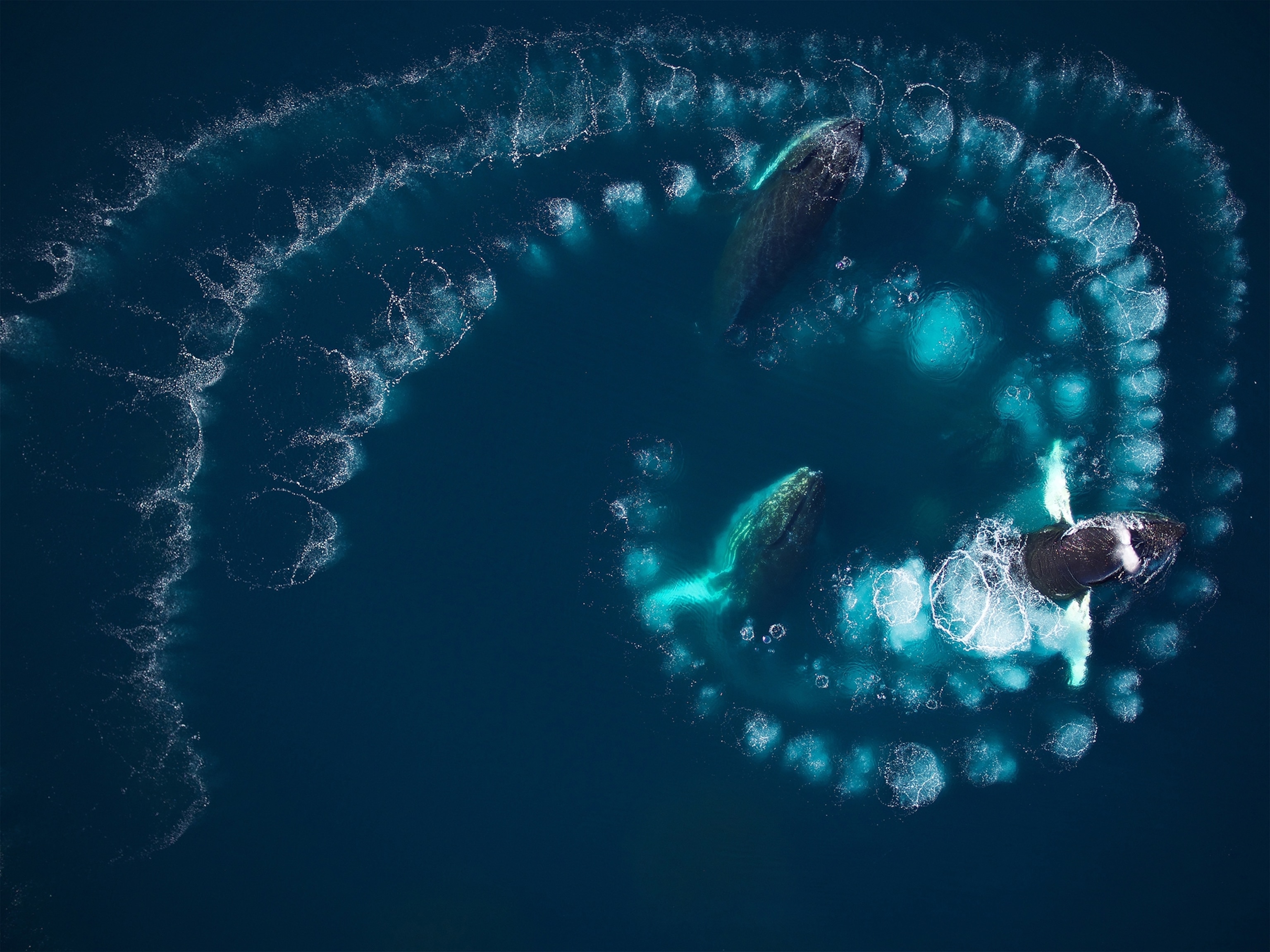

Around the world, humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) use bubble-nets to trap certain prey such as krill, herring, and young salmon, sometimes in coordinated groups and at times alone. The whales dive down below their prey and swim in circles while releasing bubbles from their blowholes to create a rising curtain. The curtain creates a visual barrier that tricks the prey into thinking there’s no escape. Once the prey is tightly corralled, the whales lunge through the bubble-net with open mouths to swallow their meal. This feeding behavior has been observed for decades, but the precise mechanics behind it are difficult to study and have long remained a mystery.

While watching humpbacks feeding “it looks like a big scattering of bubbles and it doesn't look like it's very structured,” says Andrew Szabo, a marine ecologist who leads the Alaska Whale Foundation and an author on the study. But that all changes when you add drones and underwater cameras, he says.

While tool-use in animals can sometimes be challenging to define, scientists now tend to think about describing tool use as using an external object that isn’t attached to anything to change the shape, position, or condition of something else. It’s been suggested before that bubble-netting is using a tool, but “this paper strengthens that position,” says Janet Mann, a marine mammal biologist at Georgetown University in Washington D.C. who has studied aquatic tool-use extensively.

Feeding frenzy

To get a better look at the behavior, Szabo and the team used 20-foot poles to attach specialized underwater suction tags on whales in northern Southeast Alaskan waters. These tags, equipped with 4K video cameras, hydrophones and sensors to record movement in three dimensions, as well as temperature and depth, collected data for up to 24 hours before detaching. The scientists combined the tag data with aerial footage captured by drones to precisely measure the timing, structure, and size of the bubble nets made by solitary whales.

And it turns out that these gentle giants adjust the speed and spacing of their bubble emissions to trap prey more effectively, the researchers report August 21 in Proceedings of the Royal Society Open Science. By altering the bubble rings, the whales may be able to catch seven times the prey on average in just one gulp. The whales are conserving energy, having to lunge fewer times, says Szabo, who is also a National Geographic Explorer. This efficiency is crucial for humpbacks, as they migrate thousands of miles and need to capture enough food during the summer and fall in Alaska to sustain themselves throughout the year.

“They have so much control over how they're doing this,” says Lars Bejder, another author a the study and marine mammal biologist who directs the University of Hawai’i at Manoa’s Marine Mammal Research Program. “They are increasing the frequency of the pulses as the net gets smaller, to lessen the mesh size of how the prey can escape. And that's really cool.”

For the team, humpbacks’ ability to use bubble-nets as tools speaks to the whales’ cognition and complexity, which is often overshadowed by other marine mammals, like dolphins, Szabo says. “They are remarkable animals, doing remarkable things.”

Caloric capture

Interestingly, the whales did not consistently use bubble-nets. In Alaska, only about five to 10 percent of the whales bubble-net feed. “It’s certainly the rarity, it's not the commonality,” Bejder says. “This is true in all populations, as well.”

During the three-day period when the team deployed tags, they observed 70 to 80 whales engaging in bubble-net feeding. However, just a week later, the same whales had stopped using this tactic. Why was this the case?

When and where humpback whales use bubbles may have to do with prey density. “It takes a long time to deploy these nets, and if the food is sufficiently dense where you don't need to use a net, you might actually do better not using it,” Szabo says. However, if the prey aren’t very dense, using bubble-nets allows the whales to exploit an otherwise unavailable resource. “You can actually use these nets to make something that was not profitable, profitable to feed on,” he says.

While impressive, it’s not particularly surprising, says Jan Straley, a biologist and professor emerita at the University of Alaska Southeast who has studied humpback whales since 1979. Humpback whales are known to vary where they deploy bubble nets based on prey location, environmental conditions and density. She has observed young whales learning from their moms and appear to pick up new techniques from peers.

“I think these whales are really, really good at knowing their environment and knowing the physics of their environment. They know the physical properties of the water column and how sound travels,” she says. “They're really smart for their world.”

For instance, in a region outside Glacier Bay National Park in Alaska, humpback whales feed in coordinated groups but do not use bubble-nets. Instead, they utilize tides and currents to corral fish.

In the 1980s, New England’s humpback whales developed a technique called lobtail feeding, where they slap their tails before bubble feeding. This behavior may have started as the whales changed their diet from herring to sand lance and spread through social learning.

The humpbacks' ability to change their feeding strategies and use tools to access otherwise unreachable prey might explain why they have fared better than other large whales since the whaling era. This adaptability could also give them a better chance of adjusting to climate change— as long as the prey don't disappear entirely. “Prey is declining. We know this,” says Szabo. “Whales are getting skinnier.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- What would the world look like without mosquitoes?What would the world look like without mosquitoes?

- Social media loves to villainize dolphins. Here's why it's wrong.Social media loves to villainize dolphins. Here's why it's wrong.

- How did wolves evolve into dogs? New fossils provide cluesHow did wolves evolve into dogs? New fossils provide clues

- This unorthodox method is saving baby parrots from extinctionThis unorthodox method is saving baby parrots from extinction

- A deadly disease that affects cats big and small found in U.S.A deadly disease that affects cats big and small found in U.S.

Environment

- ‘Corn sweat’—and other weird weather phenomena—explained‘Corn sweat’—and other weird weather phenomena—explained

- A sea tornado sank a yacht. We might see them more often.A sea tornado sank a yacht. We might see them more often.

- How billions of dollars are revolutionizing ocean explorationHow billions of dollars are revolutionizing ocean exploration

- Where to go stargazing in Chile according to a local astronomer

- Paid Content

Where to go stargazing in Chile according to a local astronomer

History & Culture

- Did Babe Ruth really ‘call’ this legendary home run?Did Babe Ruth really ‘call’ this legendary home run?

- The real history behind the legend of China's Monkey KingThe real history behind the legend of China's Monkey King

- How new technology transformed the American workforceHow new technology transformed the American workforce

- This secret Civil War sabotage mission was doomed from the startThis secret Civil War sabotage mission was doomed from the start

- This rare burial site reveals secrets about the Sahara's lush pastThis rare burial site reveals secrets about the Sahara's lush past

Science

- Why some say tennis is 'the world's healthiest sport'Why some say tennis is 'the world's healthiest sport'

- Your body ages rapidly at 44 and 60. Here's how to prepare.Your body ages rapidly at 44 and 60. Here's how to prepare.

- How do gold nuggets form? Earthquakes may be the keyHow do gold nuggets form? Earthquakes may be the key

- Astronauts getting stuck in space is more common than you thinkAstronauts getting stuck in space is more common than you think

Travel

- These are the must-see sights of Italy's Veneto regionThese are the must-see sights of Italy's Veneto region

- A guide to St John's, Atlantic Canada's iceberg capitalA guide to St John's, Atlantic Canada's iceberg capital