How do gold nuggets form? Earthquakes may be the key

Scientists have finally solved a long-standing mystery about the geologic process behind these large pieces of gold found in quartz rock.

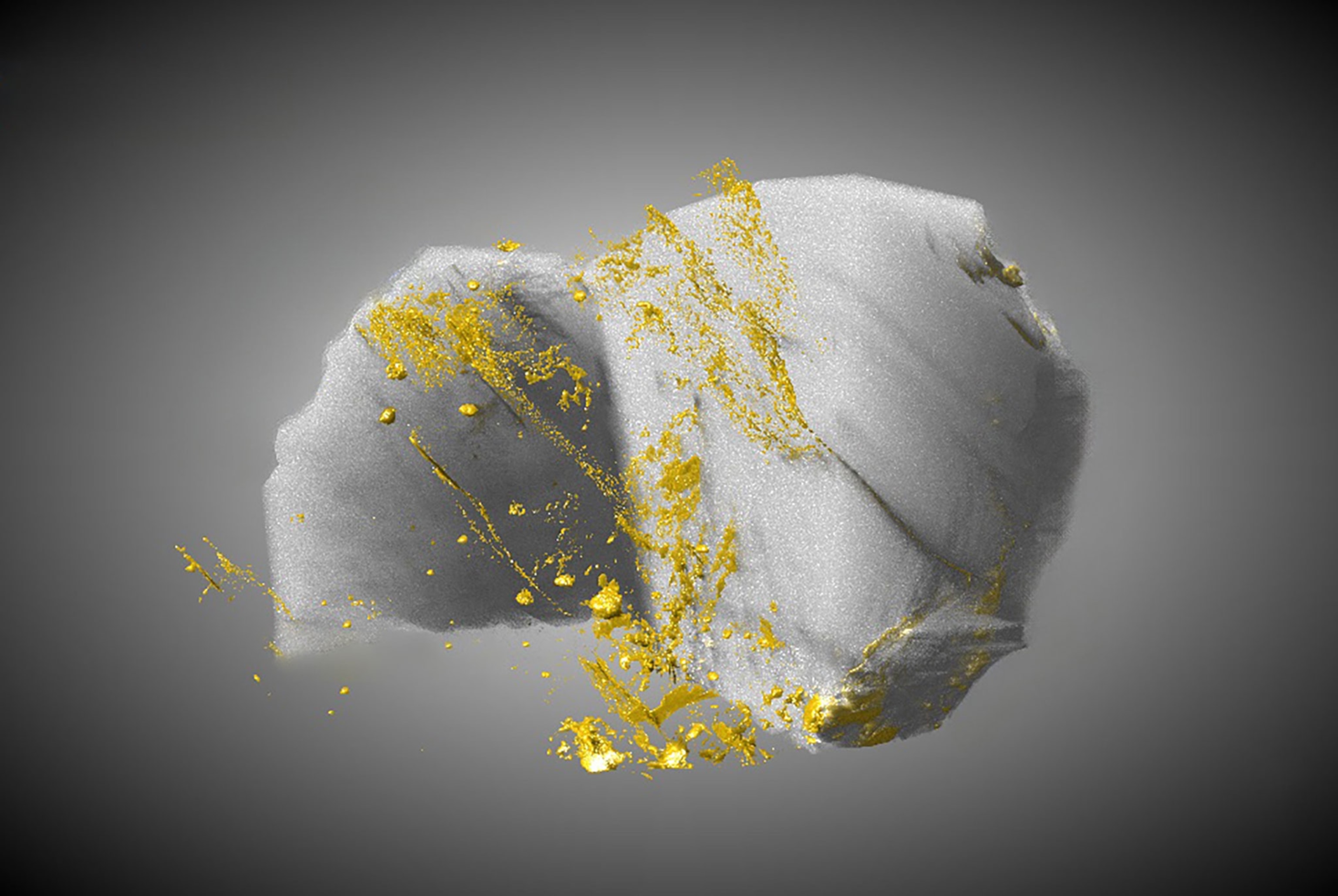

Gold has always been a hot commodity. But these days, finding a nugget isn’t too tricky: Much of the world’s gold is mined from natural veins of quartz, a glassy mineral that streaks through large chunks of Earth’s squashed-up crust. But the geologic process that put gold nuggets there in the first place was a mystery.

Now, a new study published today in Nature Geoscience has come up with a convincing, and surprising, answer: electricity, and earthquakes—lots of them.

Those nuggets owe their existence to the strange electrical properties of common quartz. When squished or jiggled, the mineral generates electricity. That drags gold particles out of fluid in Earth’s crust. The particles crystallize out as grains of gold—and, over time, with enough electrical stimulation, those grains bloom into nuggets.

“If you shake quartz, it makes electricity. If you make electricity, gold comes out,” says Christopher Voisey, a geologist at Monash University in Australia and the lead author of the new paper. Earthquakes are the most likely natural source of that shaking, and the team’s lab experiments show that earthquakes can make gold nuggets.

The idea that gold nuggets appear because of electricity instead of a more conventional geologic process is, at first, a peculiar thought. But “it makes complete sense,” says Thomas Gernon, a geoscientist at the University of Southampton in England and who was not involved with the new work. Quartz veins host a disproportionate number of gold nuggets and their environments experience plenty of earthquakes.

Cobwebs of gold

Gold is extracted from a variety of geologic deposits, but it’s frequently found within quartz veins. From afar, alabaster sheets of quartz can look like bright cobwebs weaving through rock. Gold-bearing quartz veins are found in parts of the crust that have undergone a lot of stress and strain from events like mountain formation.

These stressed, warped and fragmented areas are riddled with faults. When faults rupture during earthquakes, hot geologic fluids—sometimes containing gold particles—rush into the cracks, cool, and form gold-rich quartz veins. “It’s normally thousands to tens of thousands of pulses of [this] fluid that comes in during earthquake events then, over time, that builds an orogenic gold deposit,” says Voisey.

That gold particles find their way into quartz veins isn’t unexpected. But within these veins, miners tend to find large nuggets of gold sitting by themselves rather than just tiny grains all over the place. “How do you get such massive concentrations of gold in quartz veins?” says Iain Pitcairn, an ore geologist at Stockholm University in Sweden and who was not involved with the new work. “It’s strange and difficult to explain that.” Something must be forcing all the gold particles into specific locations, but what?

Quartz itself is also quite odd. It’s a simple mineral, made with just silicon and oxygen. But it’s also the only common mineral whose crystals lack a center of symmetry, meaning it’s structurally wonky. That means, under certain conditions, quartz’s internal electrical configuration is also imbalanced, which allows it to do something weird: create electricity.

Quartz doesn’t spark up by itself. But if you apply a force to a quartz crystal—stamp on it, say—then it generates an electric field. This phenomenon is known as piezoelectricity (which derives from piezo, the Greek word for “push”). “The more force you put in, the higher the piezoelectric response,” says Voisey. “If you hit a quartz crystal hard enough that it breaks, you’ll get the most voltage you could possibly get out of it.”

The presence of gold nuggets in veins of a piezoelectric mineral seemed suspicious to Voisey. “It’s just such a coincidence,” he says. Or was it?

Modern-day alchemy

To find out if earthquakes were the mysterious force at play, Voisey and his team placed slabs of pure natural quartz in sealed chambers containing gold-bearing liquid solutions. Some slabs were jostled about by a machine that replicated seismic waves from an earthquake. Others were left unshaken as control experiments. The hope was that gold would start appearing in a solid form atop the quivering slabs.

After the fake quakes subsided, Voisey took the quartz and looked at it under a powerful microscope. There they were: myriad gold particles, glittering across the surface.

Voisey originally had this hunch that quakes and electrical fields might forge gold several years earlier as a Ph.D. student; to see it realized was an exhilarating moment. “I went nuts when that worked,” he says. “I kicked back on my chair, screaming out and stuff. Dude, I exploded.”

As expected, the wobbling quartz had created an electrical field. The gold particles dissolved in the solution were dragged out of it and deposited as solid grains onto the quartz’s surface. But that wasn’t the end of the story. “The big conundrum is how you make really, really large gold nuggets,” says Voisey, as opposed to assorted flecks of the element.

To address this, Voisey subjected another chunk of quartz to his artificial quake machine—but this time, the quartz already a little nugget of gold in it. And when that sparkly slab was shaken up, the gold nugget began to grow.

Since gold conducts electricity, if there are gold grains already there, they act as electrodes to which gold particles migrating out of the solution are preferentially drawn. Preexisting grains and nuggets “become a lightning rod” to the rest of the gold, Voisey says.

In nature, quartz veins bearing gold nuggets are probably formed not through a single earthquake event, but by a cornucopia of them. After the first few quakes sprout grains of gold, additional earthquakes cause more and more gold particles to crystallize atop those grains, eventually forming nuggets.

“It is elegant, and it’s also really novel,” says Pitcairn.

Despite knowing exactly where to look to find gold nuggets, geologists have been baffled by their very existence. “I think this goes a long way to explaining it,” says Pitcairn.

Centuries ago, the notion that you could shake run-of-the-mill quartz about and generate gold would be considered nothing short of alchemy. This study shows that, although nature is capable of acts of magic, it just takes the right team, and the right experiment, to reveal how the trick is performed. And sometimes, the secret seems to be disarmingly simple.

“It’s almost too neat, too tidy,” says Voisey. “But I’m happy for that.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- What would the world look like without mosquitoes?What would the world look like without mosquitoes?

- Social media loves to villainize dolphins. Here's why it's wrong.Social media loves to villainize dolphins. Here's why it's wrong.

- How did wolves evolve into dogs? New fossils provide cluesHow did wolves evolve into dogs? New fossils provide clues

- This unorthodox method is saving baby parrots from extinctionThis unorthodox method is saving baby parrots from extinction

- A deadly disease that affects cats big and small found in U.S.A deadly disease that affects cats big and small found in U.S.

Environment

- ‘Corn sweat’—and other weird weather phenomena—explained‘Corn sweat’—and other weird weather phenomena—explained

- A sea tornado sank a yacht. We might see them more often.A sea tornado sank a yacht. We might see them more often.

- How billions of dollars are revolutionizing ocean explorationHow billions of dollars are revolutionizing ocean exploration

- Where to go stargazing in Chile according to a local astronomer

- Paid Content

Where to go stargazing in Chile according to a local astronomer

History & Culture

- Did Babe Ruth really ‘call’ this legendary home run?Did Babe Ruth really ‘call’ this legendary home run?

- The real history behind the legend of China's Monkey KingThe real history behind the legend of China's Monkey King

- How new technology transformed the American workforceHow new technology transformed the American workforce

- This secret Civil War sabotage mission was doomed from the startThis secret Civil War sabotage mission was doomed from the start

- This rare burial site reveals secrets about the Sahara's lush pastThis rare burial site reveals secrets about the Sahara's lush past

Science

- Why some say tennis is 'the world's healthiest sport'Why some say tennis is 'the world's healthiest sport'

- Your body ages rapidly at 44 and 60. Here's how to prepare.Your body ages rapidly at 44 and 60. Here's how to prepare.

- How do gold nuggets form? Earthquakes may be the keyHow do gold nuggets form? Earthquakes may be the key

- Astronauts getting stuck in space is more common than you thinkAstronauts getting stuck in space is more common than you think

Travel

- These are the must-see sights of Italy's Veneto regionThese are the must-see sights of Italy's Veneto region

- A guide to St John's, Atlantic Canada's iceberg capitalA guide to St John's, Atlantic Canada's iceberg capital